Your cart is currently empty!

Experiments With a Sample of n=Me

In statistics a great deal of attention is paid to proper sample size, and rightly so. There are many tools and techniques devoted to solving the problem of how many to include in your sample. Computers have made it easy to perform the calculations necessary to determine sample size.

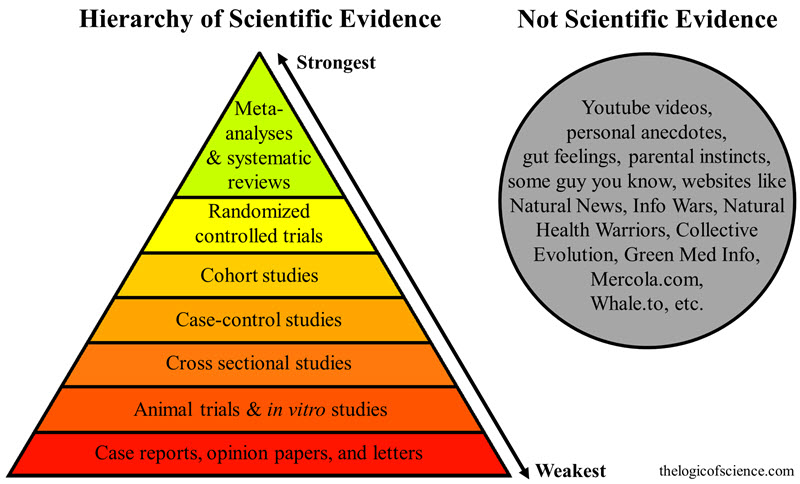

In science there is a widely accepted hierarchy of evidence (see figure above). The levels of evidence pyramid provides a way to visualize both the quality of evidence and the amount of evidence available. For example, systematic reviews are at the top of the pyramid, meaning they are both the highest level of evidence and the least common. As you go down the pyramid, the amount of “evidence” will increase as the quality of the evidence decreases. Evidence is used to assess the efficacy or safety of diets, medicines, exercise regimens, lifestyle choices, and much more. Stories or personal anecdotes are of such limited use in science that they are not even shown on the pyramid of evidence; they are shown in the circle on the right of the figure as “Not Scientific Evidence” and summarily dismissed and scoffed at. For good reason. The problem is that they don’t prove or disprove anything. At best they are “food for thought” and can stimulate creative thinking about new ideas and avenues to be explored with other research methods, perhaps using randomized controlled trials (the gold standard) or perhaps observational studies such as epidemiological studies. At worst they cloud judgment and lead to closed minds resistant to actual science.

However, I propose that conducting experiments with yourself is a special case where a sample size of 1 is enough.

Take smoking for example. I was born in 1948, a time when the majority of adults smoked. My parents, uncles, aunts, adult cousins, and nearly all of my adult role models lit up everywhere and often. So, as soon as I could, I started smoking too. I think I dabbled with the habit at age 16 and went full time after high school. This would’ve been around 1966.

I couldn’t help but notice the intense propaganda campaign against smoking by public health officials. As a typical teenaged boy I wasn’t really interested in the science or statistics surrounding the issue, but I couldn’t help notice the deleterious effects of smoking on myself, such as nicotine stains on my fingers, smokers breath, burns in my best new shirts, smelly ashtrays, and on and on. However, the habit had me by then and I persisted. Until two of my Dad’s best friends got cancer and died in their early 40s. That got my attention. That plus my constant hacking cough.

But quitting was hard and I rationalized why I didn’t need to quit. After all, I knew old smokers. Maybe I would be one of them! The turning point came at a visit with my doctor. After his examination he told me to quit smoking. I pointed out that not everyone who smoked died got cancer or died an early death. My doctor actually agreed. “Yeah, I’ve noticed that too. But you won’t last to age 40 if you don’t quit.” It was 1974 and I was 26 years of age, so 40 was already in view. I accepted that n=me was a valid sample.

I think life is about taking a little bit of risk. Following the advice of doctors also has its risks; I had a mild heart attack 15 years ago, right after getting a lab report from my doctor with her handwritten note “Great job! Keep it up!” If I’m wrong, with n=me experiments the results only affect me. But maybe this, the weakest of all evidence, can tempt you to try another amazing experiment: thinking for yourself!

Leave a Reply